Following our ten year reunion, Anita Diamant wrote this article which appeared in the Denver Post Sunday Magazine. For those of you who may have missed it, or forgotten, here it is.

“EVERYBODY HAS a reunion story,” said the man sitting next to me on the plane. I had told him that I was on my way from Boston to Denver for the 10-year reunion of the George Washington High School Class of 1969. Bob, my flying companion, had returned to Chicago’s South Side for his reunion a few years ago and he remembered it all fondly. “There was a bunch of us who used to hang around together and it was as if no time had passed at all. It was like, ‘What did you have for dinner last night?’” he reminisced over his scotches.

Somehow I didn’t think my reunion was going to be cozy. For one thing, I still didn’t know what I was going to wear; I was suddenly convinced I was grossly overweight, and I knew I had made a dreadful mistake with my new permanent wave.

Still I had made a pact with my closest friend from those days that no matter what, we would go through this thing together. We discussed it in letters and phone calls for 10 years now, and this was it: Opening Night. Or D-day. Or whatever.

I CAME TO DENVER with serious questions about the people I graduated with, the changes they had felt and made in 10 years that included the end of the Vietnam War, the bombing of Cambodia, Kent State, Watergate, the women’s movement, tax reform, Proposition 13, nuclear power, inflation and recession.

How many of us had protested against the war? How many of us had fought in Southeast Asia? How many died? Is there anything of a “generation gap” between our parents and us today? “Generation gap” was a favorite term when I was 15, 16 and 17 years old. It seemed to explain something then.

Would any of the 26 black and Oriental kids (out of a class of 946) come to a reunion where they were bound to be an even more insignificant part of the scene?

I finally decided on blue jeans and my most sophisticated shirt, got a notebook and pencils and got into the car with two high school chums for the ride to the guest ranch about 30 miles from my alma mater, where we were going to reunite.

“I WANT TO KNOW if the cheerleaders still wear their hair the same way they did in high school,” said Dr. Judith Paley from behind the wheel of her little green import. “I sure wear mine the same way.”

Leaning forward from the back seat, Sharon Long, a Ph.D. in biology doing research at Harvard, confided, “I didn’t think I was nervous about the reunion. But I had dreams about it, so I guess I was. There are all these unresolved feelings of being accepted.” In Judy’s dreams, someone kept telling her, “You’d be such a cute girl if only you’d do something with your hair.”

Almost all the women I talked to at the reunion admitted to nerves and dreams and misgivings about the day. “I wanted to be 20 pounds lighter,” said one woman, who had given birth to a baby just three months earlier. And everyone had worried about what to wear. We resolved the dilemma in multiple ways, so there were disco slides and backless sundresses, tennis shoes and t-shirts, cowboy hats and designer ponchos.

THE DISCO SLIDES ran into trouble fast when it started to rain. The organizers of this event had neglected to make plans in case of bad weather, so 200 graduates with approximately 100 spouses, children and friends in tow, huddled together under the pine trees and one covered pavilion. At first, some of the tough guys pretended it was no big deal, but once they started getting soaked and cold, we moved even closer together.

“I’m glad it rained,” said Jeff Finesilver. “Everybody had to be intimate really fast.” Once a safety for the GW Patriots’ football team, Jeff now lives in Aspen as a studio potter. Finesilver threw his first pot under the tutelage of Mark Zamantakis, who taught my class and still teaches the mysteries of clay to students at George Washington High.

Jeff was one of those people who seemed to know everyone in the class. He held court as football players-turned-salesmen, cheerleaders-turned-physical therapists and bookworms-turned-lawyers came up to greet him. “The whole thing was great,” he said later. “Just seeing all those folks. Some got fatter, some lost hair, some had a few kids. But we’re all OK. We’re all still around.”

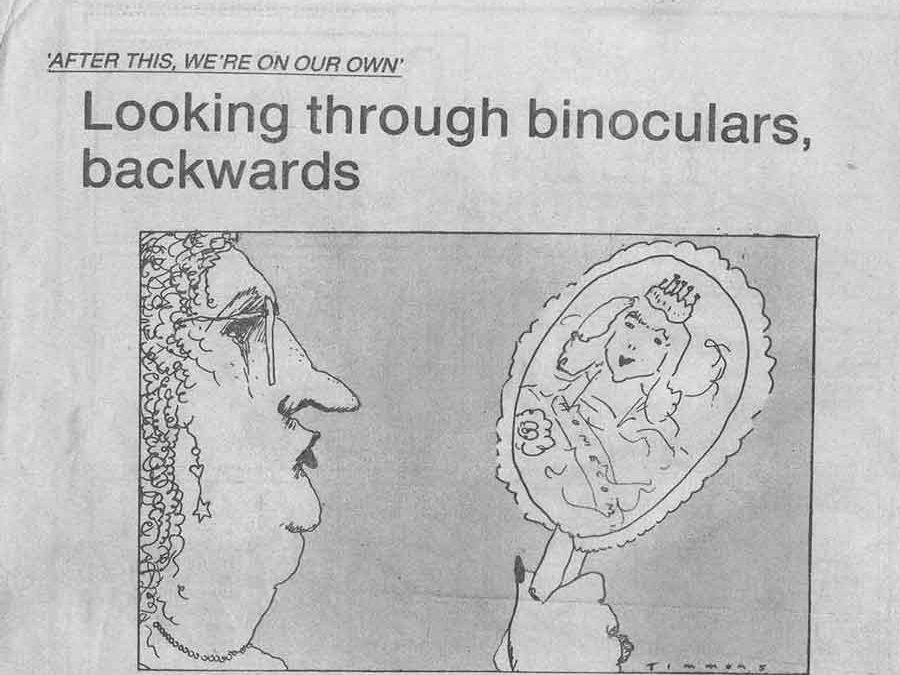

I have to admit to having more mixed feelings about being confronted with a living past. It felt a little like I was looking through binoculars backwards, so the whole sea of familiar yet strange faces looked very small and very far away.

My reunion consisted of a series of brief encounters with forgotten memories, some of them deeply satisfying, some funny, some very unsettling.

My friend Chet (Attorney) Stern, whom I see biannually, told me he talked to someone he swears he never laid eyes on in high school. “This guy came up to me and said he sold prosthetic legs in Kansas City and he thought he might run into some business at the reunion. I kept waiting for the punch line,” said Chet. “I thought he was joking!”

Things happened fast at the reunion-from the ridiculous to the sublime with the turn of the head.

ONE MAN stood near the center of the pavilion, the younger of his sons strapped to his chest. A beard and a receding hairline marked the decade, but there were the same frank eyes, the same smile – only warmer now – less hesitant. We shook hands for a long moment and smiled because it was so genuinely nice to see one another. He teaches painting to children for a living, and he paints for his soul, which from the look of him, is in good shape.

I suffered through junior high school and coasted through George Washington along side the man, Dave Parkes, whom I always considered nice and good-looking and friendly. But except for rare moments when I opened my yearbook, I never had given Dave a thought.

Yet, here he was, and there we stood, grinning at each other like Cheshire cats, feeling mutually recognized and somehow confirmed. Now when I think of the Rocky Mountains, as I often do when it’s damp and drab in Boston, I’ll remember Dave Parkes and wonder how he puts pine trees on canvas.

AND WHAT ARE you doing with yourself, I asked for the umpteenth time in 30 minutes. “Oh. I’m not doing anything much,” she said. “I have two little children and I stay with them. Nothing at all,” she said, apologizing for the hours and years of loving and care she was giving her children, her husband and her home. “That isn’t nothing,” I said. “Oh,” she said. “But I’m not doing anything exciting like you.”

Me?

I’m not a doctor, like 20 of my classmates. Or a lawyer, like another 20. Nor do I make a living at what I like doing, which is journalism. We were all pretty defensive about what had become of us. A real-estate salesman apologized to a doctor about having dropped out of premed school. “It just wasn’t me.” And I overheard a doctor dismiss 10 years of training as, “I work in a hospital.” She didn’t want to intimidate anyone.

I didn’t know Marilyn very well in high school. I did know she had a terrific bone-dry sense of humor though. She didn’t look a bit different 10 years later. What have you been up to? I asked.

I got the outline: She was divorced and had two children 7 and 9 years old. She had worked as a meter reader among other things, and her way with words still made me feel like she knew something I wanted to find out.

Someone interrupted our conversation. I turned away to ask somebody else the same questions, but I received far fewer intriguing intimations of wisdom.

Later, Marilyn came to tell me goodbye. She was drenched and cold and leaving for home and warmth. It was the biggest disappointment of the day. I wanted to find out her kids’ names and what it was like reading meters and who were her friends and what she had learned from her life.

I wanted Marilyn to tell me her secrets. But now I’d never have a chance to prove myself trustworthy.

“It’s extremely gratifying to talk to the people, to see what they’re doing,” said Bruce Dickinson, who I remember as being much jollier before he became a banker. Bruce was one of the 10 people who organized the reunion and he seemed more relieved that his job was over than to happy to be seeing familiar faces. “We just couldn’t find half the class,” he said. It’s hard since so many people have changed their names or moved away. I think how most people got here was through a friend saying, “Hey, I’m going. Why don’t you go too?” The committee had been at it since before Christmas putting ads in newspapers and tracking down addresses.

HAVING GONE through the lists, Bruce has more information on the class as a whole than anyone else. There were at least seven marriages between members of the class. But according to Bruce’s count, about one-third of the group never married. “A high percentage,” he thought.

Bruce knew of one man who served in Vietnam and came home. Five members of the class had died though, mostly in automobile accidents. One man I never knew had been shot to death driving a cab in Denver. And there were quiet rumors about suicide attempts from others. But people don’t bring their tragedies to high school reunions, and the saddest stories never get told.

One of the more unusual features of the GW Class of ’69 was seven sets of twins. The most visible duo of all was head cheerleaders Sherri and Shelly Payne. The Paynes were anxious as the rest of their classmates about the gathering. “I was nervous,” said Sherry Payne Donald, who wasn’t wearing bangs anymore, but retained her basic high school “flip.”

“It’s bringing up old ties. Why should we go back to all that? In high school I was never identified as a separate person.”

“CHEERLEADERS work, pay taxes and do like everyone else,” said Mrs. Donald, a medical assistant who lives in Littleton with her husband, a lineman for Public Service Company of Colorado. “No one even brought up the word ‘cheerleader’ to me today,” she said with some satisfaction. “People are friendlier than I expected. No one’s competing.”

Shelly Payne Mulroney, also a medical assistant, and living in Littleton, has a 3-year old son. Her husband is a fireman. “If I was asked about what I thought I expected 10 years ago, I thought I’d be married to George Philpott,” her high school sweetheart and football star. Sherri disagreed. “I expected to be in exactly the same place I am now.”

“You know, said Shelly, “in some ways cheerleading was the best days of my life.” Sherry thinks cheerleading was only second best. “It’s better now. This is more real.”

THE CLASS OF 1969 includes a couple of writers, a belly-dancing librarian, a number of therapists and psychologists, artists, real-estate agents, carpenters, cops, business people, secretaries and even the 1970 Miss Colorado, Cathy Glau (who didn’t make an appearance at the reunion).

I put my pencils and paper away half an hour after I got to the reunion of the GW Class of 1969. I wasn’t going to be able to answer any abstract questions about this group of 27- and 28-year old adults, all of whom looked like long-lost cousins, all of whom looked like total strangers. This wasn’t the time or place to take the pulse of America, to compare generations, or to ask open-ended questions.

Reunions are for measuring your own changes, the distance between today and high school when you, we, I all felt so adult, so ready to get out there and Do Something. When we were so nervous about being judged by our peers that we had nightmares and acne and cruel jokes to spare.

I HARDLY CAN remember who I was in high school. I know I was in every single play and musical performance that happened at GW for three years; so naturally, I was asked if I still was into theater. But I hardly ever go to the theater these days, much less take part in it.

Did I do anything with my French? a classmate asked me. Besides forgetting most of what I knew? No.

But no one seemed to have forgotten what I looked like, even with chemically curled hair. Nor had I forgotten the faces of the people in the chorus, the pep club, the football team.

Denver has become a big, smoggy city and my parents moved away last year. I’ll have a weakness for the Rockies until I die, but Denver isn’t home anymore. Yet here I was in the small-town community that happens at everybody’s high school, even if now there are policeman guarding the doors. Even if you take a bus from across the city to get there. Even if you hated it while you were there.

BRUCE DICKINSON said, “It’s fun to have roots.”

After 4½ hours of soggy hellos and goodbyes, Sharon, Judy and I drove back to Denver through one of those perfectly brilliant, crystal, after-the-storm mountain sunsets. We exchanged gossip about the way people looked and the things they were up to and we shared information about people who hadn’t come and we were quiet for long minutes at a time.

Finally, Sharon broke the silence: “It sort of closes your identification with high school and your class. You evaluate yourself in comparison to where you came from.”

“It seems to me,” she said, wistfully, “that after this, we’re on our own.”

Thanks, this was great to read!!

Always an interesting read from Anita! Looking forward to the one she writes about our 50th.

Thank you so much for posting this- I wasn’t able to attend our 10th( I just had a baby) but I was at our 20th!

This is a very meaningful article,sad since Cathy Glau, the Payne twins and so many others I knew all are dead now-I feel grateful to be able to attend our 50th, part of me feels I owe it to our friends who have passed,to share our memories and talk about our classmates that we wish were there!

How beautifully written. You can’t go home again? I don’t know… maybe with time comes the wisdom of age, acceptance, forgiveness, and the joy and excitement of life. Kevin Fitzgerald GW 1969

How beautifully written. You can’t go home again? I don’t know… maybe with time comes the wisdom of age, and with that comes acceptance, forgiveness, and the joy and excitement of life. Kevin Fitzgerald GW 1969

It was really fun to read this and think back to that (a bit doomed) reunion. Scott and I had to employ three grandparents to take care of our 2 year old and 2 month old at his luckily nearby family cabin! I had to go back half way through to nurse the baby. It seems like ages ago and just yesterday. I’m sure this one will be bitttersweet, and memorable. Not to mention dry!

Reading this I was struck how things were and hasn’t changed today.

“People will forget what you said.

They forget what you did.

But people will never forget how you made them feel.”

Maya Angelo

We were all members of the class of 1969. Each individual made a contribution.

Dan Dinner

I throughly enjoyed the 10 year Reunion story and recap.

I did not attend. My self esteem and desire to go was

not present. I was married with my first of 3 daughters.

Fast forward to the 50th Reunion, I wouldn’t miss it for the world. See you next month!